| |

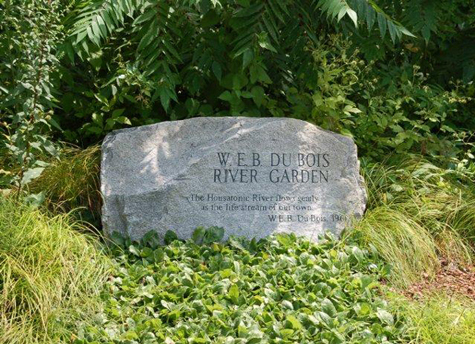

I know the Housatonic by its native flowers, from the first blush of shadbush to the last purple asters that withstand the frosts of fall. I know spring by vernal pools and the unmistakable clamor of peepers, summer by the ferns that green the banks. In autumn, the river sparks metallic, reflecting golden sugar maples and the deep steel-blue of sky. In winter, the river's dark, brooding power rolls below sheets of ice. Long after the Mahican people settled here, the Housatonic became a "working" river. Early European settlements became attractive towns and tidy cities, as modest gristmills grew into substantial paper and textile mills and ultimately into modern industrial plants. It was a time of denial, for the Housatonic, however, as its towns were built with their backs to the river, and the river fell prey to abuse and discarded waste. Although nineteenth-century artists such as Thomas Cole (1801–1848) and Frederick Edwin Church (1826–1900) revealed the river's essential beauty, others, including Unitarian minister John Coleman Adams (1735–1826), saw in the Housatonic "a noble example of how hard a river dies."1 Another early advocate for the Housatonic River was Great Barrington native William E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963), the father of Pan-Africanism and champion of American civil rights. "I was born by a golden river," he wrote of the Housatonic, and campaigned for its recovery throughout his life:2

Du Bois's pioneering vision tied the fate of all rivers to environmental health, social justice, and human rights. He advocated for the care of river-landscapes around the world, imagining peoples of all races and vocations coming to their aid to shape the destiny of rivers and their own. Today, the Housatonic is winding its way back into the hearts of its towns and cities, in an evolving story of stewardship and renewal. Twenty-five years ago, a contingent of twelve local residents undertook the daunting task of clearing remains of a burned-out building from the banks of the Housatonic in downtown Great Barrington. Since then, 2,400 volunteers have reclaimed and transformed the town's once-ravished riverbank into River Walk, a half-mile of trail and wetland gardens that meander along the river's edge.4 Like much of New England's landscape, its beauty is more handcrafted than wild. When towns and cities reclaim abandoned rivers, a rich historical and natural heritage is revealed underfoot. There is a new regard for wildlife habitat, native flora, vistas and views, avenues of transport, geological formations, wetland and floodplain ecology, historic and prehistoric patterns of human settlement, and local legend. Rivers are places of confluence where culture and nature intersect; they cannot be separated from the people who live by them. 1. Adams, John Coleman, Nature Studies in Berkshire (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1901), 110. Copyright © 2013 Rachel Fletcher. All rights reserved.

|